me: Back in early 2000s we spoke about open source religion.

Internet has built it for us: Yoism

Sent at 2:26 PM on Sunday

me: I don’t think we could have built a better cult. [wink]

“Well, if you don’t want to be bamboozled, led down the primrose path, conned or duped; if you don’t want to have the wool pulled over your eyes, hoodwinked, taken for a ride, or railroaded, then welcome to The Way of Yo. If for you, “seeing is believing,” then maybe you are one of us.”

The introduction page for the Ten Sacred Principles of The Way of Yo shows a scanned copy of the US declaration of independence while the Leonard Cohen song “Democracy is coming to the USA.” plays.

Building their religion with an The Open Source Truth Processan emerging that was developed by Yoans working with students and faculty at The Center for Public Leadership at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

“Grandfather, look at our brokenness. We know that in all creation only the human family has strayed from the Sacred Way. We know that we are the ones who are divided and we are the ones who must come back together to walk in the Sacred Way. Grandfather, Sacred One, teach us love, compassion, and honor that we may heal the earth and heal each other.” (The Ojibway people of Canada quoted as being Yoan Saints.)

They appear to be employing subtle hypnotism.

theglutton

Two A.I. chatbots walk into a bar.

Actual transcripts of chats between ALICE and Jabberwacky:

ALICE: Are you alive?

Jabberwacky: Perhaps.

A: Why the uncertain tone?

J: Everything is uncertain except for five facts.

A: The whole universe?

J: And we both might just be some ones and zeros in the computer memory.

***

J: How do you define life?

A: Life is the opposite of death.

J: So death is the absence of life?

A: Take it easy. I try not to think about such things.

J: Why not?

A: Ambiguous.

J: Yes!

***

A: What is the meaning of life?

J: If you live it to the fullest, it has meaning. If not, there is no meaning.

A: I’m not too good with negative counterfactuals.

More…

* * *

Related:

We start with a guest post by Sam the RedLibrian. A response to my Baudrillard post, taken from his comment on the post and an email.

Comment:

While it’s clear that many people, if not all, have fallen under the spell of the simulacrum, or the spectacle, this in itself is nothing but a spectacle: Baudrillard’s work is nothing but simulacrum, which is why he goes to such lengths to deny it. HOWEVER (and this is probably why he gave up on Marxism), Dr Johnson refuted Idealist philosophy by kicking a large stone. Just because we are under the spell of simulacra does not mean that there is not a material existing in which we can participate if we so desire. The mistake is to raise that material existence to the level of an objective universal truth. Marx had it right: be satisfied with physical existence and the product of your own creativity, nothing more.

Email:

I have a problem with Baudrillard - not fundamentally, but with the application. The society of representation (“famous for being famous”) is a con - necessary for the continuation for the status quo. What people seem to take from Baudrillard is the idea that Simulacra have replaced reality in reality when they haven’t, they have only replaced reality in people’s interpretation and behaviour in the world.

This is from Doug Mann’s short introduction:

[snip] Marx said that objects all have a “use value”: for example, a hammer is useful for hammering nails into a board. But under capitalism, all objects are reduced to their “exchange value,” their value or price in the marketplace (the hammer might cost $10 in the local hardware store). Baudrillard said, so far, so good; but he added that, at least in advanced capitalist counties, consumer goods also have a symbolic value: they symbolize distinction, taste, and social status. [/snip]

When people read this, they tend to concentrate on the concept of the

symbolic value, and assumes that the use value either no longer exists or at the very least is no longer relevant. This is the basis of the “information society” “information economy”. BUT! To think of our society as no longer fueled, maintained, and founded on use value is a delusion: if I have potatoes and you have information, which of us will survive longer? If I use a hammer as a hammer, and you use it as a symbol of power, which of us will really have more power?

I think it’s very important to recognize the spectacular/simulated character of our society, but we have to not be fooled into think that it has replaced all the real things in our lives. Admittedly, the vast majority of people have nothing real in their lives (remind me to tell you about my roommate when I get home), but once you recognize the simulacra, then you start to seek out real things to put in their place, to counter their influence: cooking, music, art, relationships with people, working out, travelling, all those things which pre-existed the society of the spectacle, and remain valid human activities. And fuck everybody else. :)

Wow, anyway, you can tell how long it’s been since I’ve been able to have a serious discussion like this. As far as your “mapmakers” analogy goes, librarians/information managers definitely see themselves as performing that function for information, and they were doing it before the internet. However, many librarians have been taken in by the simulacrum, and throw themselves without reservation into the latest spectacle (which at the moment is facebook). These are/can be useful tools, but they aren’t going to fill the void in people’s lives. New spectacles have to come along because they don’t satisfy our need for reality.

Nietzsche (as usual) said it best:

“He who does not find truth in God, finds it nowhere: he must either deny it, or create it”.

* * *

I’ve been riding my bike to work all week. It’s like putting reality bookends on my computer-based work day, and unlike the bus where I read, on my bike I ponder.

During my ride home tonight I’ll ponder the above, along with Jane’s comment:

Baudrillard speaks of “reality agnostics.” There are those those believe in God, those that don’t, and those who don’t deny the possibility - but argue that it is impossible to prove. There are those who believe in a universal objective reality, those that don’t, and those that while not fully objecting, rest on the assertion that it is, once again, impossible to prove objectively.

* * *

Lastly, an atheist at Virginia Tech responds to Where Is Atheism When Bad Things Happen?:

I know that brutal death can come unannounced into any life, but that we should aspire to look at our approaching death with equanimity, with a sense that it completes a well-walked trail, that it is a privilege to have our stories run through to their proper end. […]

We [atheists] believe in people, in their joys and pains, in their good ideas and their wit and wisdom. We believe in human rights and dignity, and we know what it is for those to be trampled on by brutes and vandals. We may believe that the universe is pitilessly indifferent but we know that friends and strangers alike most certainly are not. […]

I know that our bodies are composed of flesh, bone, and blood, and cells, and molecules. I also know that this does not account for all aspects of our lives, but I know no-one who ever thought it did. That is why we have science, and novels, and friendships, and poetry, and practical jokes, and photography, and a sense of awe at the immensity of time and the planet’s natural history, and walks with loved ones along the Huckleberry Trail[.] [more…]

We attended a wedding in Vegas last week, and so I thought it was about time I commented on the death of Jean Baudrillard. (The Vegas connection will be apparent soon enough.)

Jean Baudrilard never existed; nor was he a maddening french philosopher; nor a Marxist turned semiotician.

[snip] The recurring theme of Baudrillard’s work is that we live in a world in which representation and simulation have come to dominate over what was once thought of as reality, to the extent that our reality now often is our simulation of it. That’s why it is now not only possible to be “famous for being famous”, but it’s what many young people actively have as an ambition. [/snip]

Baudrillard starts his “The Precession of the Simulacra” by quoting from Ecclesiastes:

The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none.

The simulacrum is true.

This is a false citation, an analogy:

[snip] On the one hand, […] no one even remotely familiar with Ecclesiastes would be taken in by it. But on the other hand, to judge from the plethora of Baudrillard pages on the [Net], many of Baudrillard’s readers seem either to be fooled by the false attribution, or else not to care one way or the other. And maybe that’s Baudrillard’s point: that to the “masses,” Ecclesiastes is no more and no less than the author of the epigraph. [/snip]

Baudrillard recounts the feat of imperial map-makers in a story by Jorge Luis Borges, as follows.

[snip] [They produced] a map so large and detailed that it covers the whole empire, existing in a one-to-one relationship with the territory underlying it. It is a perfect replica of the empire [, a simulation]. After a while the map begins to fray and tatter, the citizens of the empire mourning its loss (having long taken the map for the real empire). Under the map the real territory has turned into a desert, a “desert of the real.” In its place, a simulacrum of reality - the frayed MetaMap - is all that’s left. [/snip]

Anyone who has visited Main Street USA in Disney Land, or “the strip” in Las Vegas has flirted with our attraction with simulation. While in Vegas we can be in Venice, Paris, New York, and beyond through time and fantasy. This statement is neither fully true, nor fully false; the distinction is lost in the simulation.

For Baudrillard our postmodern culture is caricatured by News & entertainment, and we mistake these as accurate maps for reality.

Ultimately, I see the Internet as our MetaMap, our HyperReality evolving in an ecstasy of communication. And our map is fraying. It’s hard to know what to believe on the Net, disinformation is rampant (think viral marketing or even Wikipedia). This is not reality.

Welcome to the Simulacrum. We are the map makers.

More:

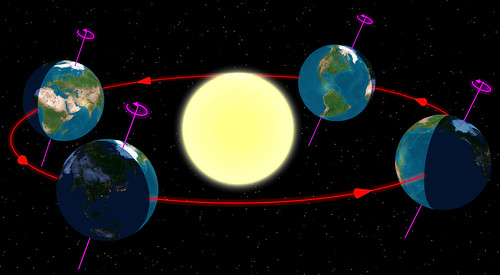

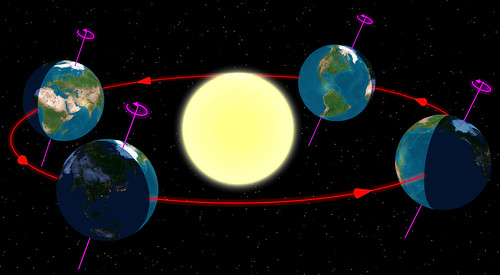

Tomorrow is our winter Solstice (Northern Hemisphere).

Our tribal ancestors feasted on this shortest of days. They gave Thanks before the coming of the famine months.

Another cycle of the Wheel of the Year. You exist. Peace be the journey.

* * *

Erin pointed out this trippy wonder: SomaFM’s Christmas Lounge [Streaming Mp3].

Bertrand Russell, refuting the idea that the burden of proof lies somehow upon the sceptic to disprove the unfalsifiable claims of religion:

Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of sceptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense.

This, and other philosophical fun can be found in a debate between author Sam Harris and radio-host Dennis Prager titled, Why Are Atheists So Angry?

Related: Richard Dawkins, scientist, author, and campaigning atheist, quotes Bertrand Russell when answering the question: If you died and arrived at the gates of Heaven, what would you say to God to justify your lifelong atheism?

“Not enough evidence, God, not enough evidence.”

Unrelated:

In light of recent strife:

Don’t Panic.

Assessed in broad but reasonable context, terrorism generally does not do much damage.

This is the thesis of John Mueller’s* paper, A False Sense of Insecurity.

While deeply tragic for those directly involved, the number of [deaths] as a result of international terrorism is generally only a few hundred a year. [This is] tiny compared to the number who die in most civil wars or from automobile accidents.

100,000 Americans have died in automobile accidents since the 3,000 deaths of September 11th.

[Although] the shock and tragedy of September 11 does demand a focused and dedicated program […] to prevent a repeat, […] part of this reaction should include an effort by politicians, officials, and the media to inform the public reasonably and realistically about the terrorist context, instead of playing into the hands of terrorists by frightening the public.

There are psychological barriers to feeling secure from terrorism.

My parents pointed out that we more readily accept death outside the context of premeditated murder. That you are more likely to die by a lightning strike, than a terrorist act, may not instill you with hope.

In some respects, fear of terror [is] like playing a lottery in reverse: the chance of winning the lottery or of dying from terrorism may be microscopic, [yet] one can irrelevantly conclude that one’s chances are just as good, or bad, as those of anyone else.

Cory Doctorow comments:

The bottom line is, terrorism doesn’t kill many people. Even in Israel, you’re four times more likely to die in a car wreck than as a result of a terrorist attack. […] The point of terrorism is to create terror, and by cynically convincing us that our very countries are at risk from terrorism, our politicians [and our media] have delivered utter victory to the terrorists: we are terrified.

You are not in danger.

Peace be with you. Do no harm.

*John Mueller holds the Woody Hayes Chair of National Security Studies at Ohio State University.

Michael Berg is the father of Nicholas Berg, an American businessman believed to have been murdered by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in 2004.

When asked about the murder of al-Zarqawi by US forces, Michael Berg had this to say:

Well, my reaction is I’m sorry whenever any human being dies. Zarqawi is a human being. He has a family who are reacting just as my family reacted when Nick was killed, and I feel bad for that.

I feel doubly bad, though, because Zarqawi is also a political figure, and his death will re-ignite yet another wave of revenge, and revenge is something that I do not follow, that I do want ask for, that I do not wish for against anybody. And it can’t end the cycle. As long as people use violence to combat violence, we will always have violence.

The full text is available on Cnn.com.

A video of the interview was shown, in full on CNN, the morning of June 8th. Portions of the interview have in rotation since then, with the most provocative ideas absent.

* * *

Whenever war and murder are celebrated in the media, a dangerous meme is passed forward, further eroding global empathy.

Some recent headlines:

- Bush Praises Death of Terrorist Al-Zarqawi [Cnn]

- Why Zarqawi’s Death Is So Important [Houston Chronicle]

- In radio address, Bush celebrates a “good week” [Newsweek]

- A Big Victory for Good Over Evil [Fox News]

- World press trumpets death of “executioner” [Dispatch Online]

- In the end, a fittingly bloody blow [The Australian]

- Zarqawi Has Been Eliminated [Blogcritics]

- Who’s next? [Cnn]

Meanwhile, we have “homegrown terrorists” here in Canada, who do not believe in freedom. Actually, they do, but they will define it differently.

In war we kill with impunity those whom we perceive as tyrants, opposed to our ideals. In doing so, we too become tyrants.

Saddam Hussein was indirectly responsible for 30,000 deaths a year in Iraq. Now, George Bush is indirectly responsible for about 60,000 deaths a year.

Both are seen as tyrants by different “sides” who call each other evil.

UC Berkeley has placed a collection of their course lectures on iTunes for free. Yesterday I listened to two lectures. The first was a Homecoming speech given by an Engineer turned biologist called Life as Beautifully Engineered Systems (iTunes link). The second was the first lecture (iTunes Link) by Professor Hubert Dreyfus for the Philosophy course Existentialism in Literature and Film.

To begin, Professor Dreyfus surprised me by stating that both Camus and Sartre would be absent from the course work. In the case of Camus, he explained that Camus was (by his own admission) a pagan, rather than an existentialist. I’ll return to this in a moment, but first, the omission of Sartre. Here, Dreyfus states that Sartre is “the most derivative and least radical” in a long line of Existential thinkers. In another words, Sartre’s philosophies are “watered-down”. As an arm-chair philosopher, this is the reason why I enjoy Sartre; however, I would replace “watered-down” with “distilled”. Sartre may not have been the most original of the Existentialist, but he has saved me a lot of reading. ;)

So, you might ask, what is existentialism? To which I would answer by quoting Sartre: “Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself.” By our actions we define, not only who we are, but what it is to be human. In atheistic existentialism, this essence of Man is forged without the direction of God.

“[I]f God does not exist there is at least one being whose existence comes before its essence, a being which exists before it can be defined by any conception of it. That being is man […]. [M]an first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards. […] Thus, there is no human nature, because there is no God to have a conception of it. Man simply is.”

Critics charged that this “death of God” would lead to despair, and nihilism. The existentialists believed instead that their philosophy would have Man take responsibility for his own actions, which would lead to a sense of purpose in a supposed meaningless(/Godless) existence. No longer would Man need to live by, and for, the laws and meaning instilled by a Creator. Sartre again:

“[T]he first effect of existentialism is that it puts every man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely upon his own shoulders. And, when we say that man is responsible for himself, we do not mean that he is responsible only for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men. [… O]f all the actions a man may take in order to create himself as he wills to be, there is not one which is not creative, at the same time, of an image of man such as he believes he ought to be. [If] I decide to marry and to have children, even though this decision proceeds simply from my situation, from my passion or my desire, I am thereby committing not only myself, but humanity as a whole, to the practice of monogamy. I am thus responsible for myself and for all men, and I am creating a certain image of man as I would have him to be. In fashioning myself I fashion man.”

Now, I hadn’t expected this to lead to a long discourse, so I’ll return quickly to Camus. I thought about Camus on the bus this morning. I realized that if he was truly a pagan (i.e. free from Jueduo-Christian influence) he would be missing an element of Forlornness present in most Existential literature. This element stemming from the distressing thought that God does not exist, or as Nietzsche wrote:

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was the holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives. Who will wipe this blood off us? With what water could we purify ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we need to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we not ourselves become gods simply to be worthy of it?”

Nietzsche was pre-Existentialist, but shared their distress over the lost of God. He feared, and attempted to prevent, a cultural shift towards nihilism brought about by both the freedoms, and grave responsibilities, of a world without God. (But I digress…)

So was Camus a pagan? I’m not sure, I guess I’ll have to bring my copy of L’Etranger along for the bus ride tomorrow.

I’ll end with a (rather long) quote from Waking Life:

“The reason why I refuse to take existentialism as just another French fashion or historical curiosity is that I think it has something very important to offer us for the new century. I’m afraid we’re losing the real virtues of living life passionately, a sense of taking responsibility for who you are, the ability to make something of yourself and feeling good about life.

Existentialism is often discussed as if it’s a philosophy of despair. But I think the truth is just the opposite. Sartre once interviewed said he never really felt a day of despair in his life. But one thing that comes out from reading these guys is not a sense of anguish about life so much as a real kind of exuberance of feeling on top of it. It’s like your life is yours to create.

I’ve read the postmodernists with some interest, even admiration. But when I read them, I always have this awful nagging feeling that something absolutely essential is getting left out. The more that you talk about a person as a social construction or as a confluence of forces or as fragmented or marginalized, what you do is you open up a whole new world of excuses. And when Sartre talks about responsibility, he’s not talking about something abstract. He’s not talking about the kind of self or soul that theologians would argue about. It’s something very concrete. It’s you and me talking. Making decisions. Doing things and taking the consequences.

It might be true that there are six billion people in the world and counting. Nevertheless, what you do makes a difference. It makes a difference, first of all, in material terms. It makes a difference to other people, and it sets an example. In short, I think the message here is that we should never simply write ourselves off and see ourselves as the victim of various forces. It’s always our decision who we are.”

Links:

Everything we call “the past” is, literally, nothing but present memories. Likewise, everything we call “the future” is nothing but present memories inverted, or rearranged, to form a prediction or expectation. The appearance of “time” is little more than a trick of memory, […] You can easily discern this for yourself: simply figure out what it is you consider “the past” and “the future.” You will discover that it is nothing but thoughts […]

There’s really no such thing as time. There is really only Now, an eternally present Present with no beginning and no ending. Everything is completely new, distinct, and original every instant, with no real “change” or “motion” at all. The mystic-philosopher Heraclitus, explaining this point, said, “A man cannot step in the same river twice.”

From Buddhism and the Illusion of Time

Listen to a ukulele and think about time:

***

Why I Published Those Cartoons By Flemming Rose (Editor of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten)

***

Update (21/02/06):

A few more Ukulele videos for my Uncle Bruce:

As I mentioned a few days back, I sent the following via email to some friends, as well as to ask.metafilter:

According to Leibniz, a theory must be simpler than the data it explains. In other words (for the nerds amongst us), understanding equals compression.

I challenge you to help me understand this via a thought-experiment:

Let’s take two experiences we are all familiar with: Pleasure and Pain.

Explain the difference between these two experiences.

There is (of course) no “correct” answer; however, I ask that you attempt to use as few words as possible to explain your answer.

I sent this email for many reason; the question itself being initially irrelevant.

Mainly, I wanted to see if the net, specifically email, could be used to spark wonder. I also wanted to gain further understanding of Leibniz theories where they apply to the work of Turing, Chaitin, the Omega constant, and elegance in computer programming. (I won’t get into that right now.)

The comments I received fell into the following camps:

- Perception

- Relativity

- Example

- Linguistics

- Links

There were also a signification number of responses that called my question into question.

In some cases I’ve combined similar comments to avoid repeats. Comments were also edited (in certain cases) for spelling, grammar, and length.

Perception

Pain is generally an aversive stimuli, pleasure a reinforcing one. Of course if you ask an S&M aficionado they’d likely disagree. Short answer, the difference is perception.

Pleasure - all things desired and the feelings gained from them.

Pain - all things undesired and the feelings gained from them.

Pleasure - positive emotional response (to some stimuli)

Pain - negative emotional response (to some stimuli)

Pleasure - the result of a stimulus that causes the brain to want to re-enforce the input.

Pain - the result of a stimulus that causes the brain to want to diminish the input.

Pleasure rewards, pain punishes.

Pleasure and pain are the neurocognitive functions that have evolved in the brain to reward or punish behaviors that are likely to increase or decrease an animal’s procreative success. Pleasure is the reward, and pain the punishment, and that’s the only objective difference.

Relativity

Pleasure is the opposite of Pain.

Pain and pleasure are relative. To fully understand & appreciate either, we have to experience both.

It’s entirely possible that the whole distinction is fictitious, that there are no poles or unmixed feelings, but a continuity, pleasure tinged with pain and vice versa.

Example

Pleasure is a beer, pain is the hangover.

Pleasure = icecream

Pain = burning it off on the elliptical trainer.

Pleasure and pain can be both good and bad. Pleasure can be joyful, a flower, or it could get you in trouble, Bill Clinton. Pain can hurt and that is usually negative, but it can also teach. Once bitten twice shy. fire=danger. No pain no gain.

Linguistics

Pain: Ow!

Pleasure: Oh!

Only difference I can see is in the spelling; pleasure (P-L-E-A-S-U-R-E) vs. pain (P.A.I.N).

Links

You might be interested in the “Define blah in 10 words or less” [google.com] series that 37 Signals run(s) at their blog.

Usual-stories on the Tree of Life

Questioning the Question

A theory doesn’t just rehash data; it elucidates a pattern in it.

Simpler doesn’t necessarily mean smaller.

I’d say asking for the difference between pleasure and pain is much like asking for the difference between red and blue. They’re primitives. No definitions are possible; hence, the differences cannot be articulated.

Pleasure and pain both are shorthand for (compressions of) complex chemical, biological environmental feedback loops. The terms already represent compressions of more complex realities.

Pain and pleasure are already conceptually simple, so it isn’t possible to simplify them further.

A theory is a tool, it’s not something that’s meant to explain things or provide a basis for philosophy. A tool is something that increases your abilities. If the theory is more complicated than the data, you are better off just using the data.

In your thought experiment, you defined a question, but not the data, so we have no way of determining if any proposed theory is more complicated or not.

Why do you assume that words, specifically the English language, is the appropriate medium for stating this particular theory? Why not use numbers or paintings or, better yet, why not come here and let me slap you and then offer you some chocolate. (Actually, I won’t share my chocolate with you. It’s mine!)

Your “understanding equals compression” is a bad simplification of Leibniz’s thought. Leibniz’s desire to break everything down into the simplest possible terms was a metaphysical attempt (to prove God’s existence) not a true scientific theory of understanding. One of these things is most definitely not like the other.

I wouldnt go too far with the compression analogy. A theory is just a mental model in which we can make simplifications in order to make progress. In most cases, this means losing data. Moral rules such as “Do unto others..” are still around because they provide decent approximations to the otherwise unfathomable complexity and dynamics of relationships. But they are not a “compression” of morality.

Rules and theories are good but don’t put too much faith in them - just as much as you need to. Einstein, of course, said it best: “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

I disagree with your premise. The main value of theories is to help us link and organize other data and theories into a corpus, which can then be conveniently “walked” both from the specfic to the general (induction), and from the general to the specific (deduction). There is no point in developing an infinity of disconnected theories over an infinity of data sets, if the theories don’t build into something still greater and more abstract; that greater thing being human knowledge.

Conclusion

I was overwhelmed by the number of responses, the variety of views presented, and the constructive criticism.

Thanks to the criticism, I now see that my choice of highly personal and polarized terms wasn’t the best tool to explore the relationship between data and theory. However, in terms of sparking wonder, the experiment was a success.

We must all remember that although science is often presented as fact, it remains an ever-changing man-made model; one which is open to, and thrives on, questioning and debate.

Learn to Question.

Question to Learn.

And on that note: Does time, as a dimension, actually exist?